TD Economics Special Report on Financial Vulnerability of Canadian Households: BC Most Vulnerable

TD Economics released a special report on February 9th, 2011. This report assesses the financial vulnerability of households across Canada. Below, I have included British Columbia specific information from the report. Click on the images below to enlarge.

The main highlights of the report are:

- The focus nationally on household debt has raised questions about which regions of the country face the most significant challenge.

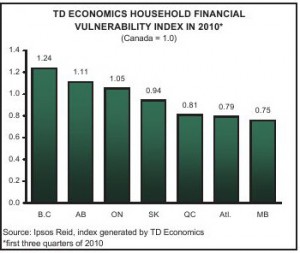

- TD Economics has constructed an index of financial vulnerability, which takes into account six key metrics of household financial position.

- The index is not a predictor but is aimed at capturing which regions are more vulnerable in the event of an unexpected adverse economic shock, such as a housing market downturn, a rise in the unemployment rate, or a spike in interest rates.

- We find that households in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan are the most vulnerable, followed by the Quebec and the Atlantic Region. Meanwhile, Manitoba is the least vulnerable.

- Despite growing vulnerability across regions, we do not think that a household debt crisis is in the making in any region.

Based on our analysis, we find that households in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan are the most vulnerable. Following next are the Atlantic region and Quebec, while Manitoba is the least vulnerable. That being said, risks related to household finances have been rising broadly across all regions over the past few years, as households have responded to extremely favourable borrowing conditions. With higher interest rates on the horizon set to boost the cost of servicing debt, this upward trend in vulnerability is almost certain to continue over the next 1-2 years.

All regions increasingly vulnerable

Some of the common trends:

- Vulnerability has been increasing from coast to coast over the past two years– prior to 2009, trends in the vulnerability index were mixed across the country, with some regions experiencing sharp increases while others registered declines. However, over the past two years, vulnerability has headed higher right across the board, and for the majority of regions, increases in the index began to accelerate in 2007.

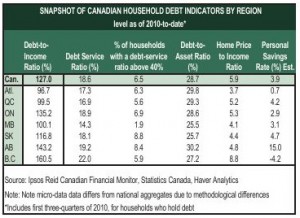

- Rising household debt-to-income and home price to- income ratios have been the major catalysts driving up vulnerability – the debt-to-income ratio has followed an upward track in all regions since the mid-part of the 2000’s, reflecting in large part the strength of housing markets and the significant easing in mortgage insurance rules in late 2006. These home price increases supported the asset side of the ledger and mitigated the upward trend in the debt-to asset ratios over the past half decade.

- Debt-service ratios have been falling and remain in a comfortable range – despite rising indebtedness, the falling cost of borrowing has been pulling down the share of income households have been shelling out to service obligations. Low interest rates have also helped to keep a lid on the share of vulnerable households in recent years.

- All regions will experience a substantial increase in vulnerability over the next few years – our adjusted index shows that even assuming that the debt-to-income ratio holds constant at current levels, which would seem unlikely, vulnerability is set to rise across the board in lockstep with short-term interest rates.

Most vulnerable

Reflecting the lofty costs of home ownership, households in British Columbia record the highest vulnerability. In particular, B.C. residents on average register the highest debt-to-income ratio, debt-service cost, and greatest sensitivity to rising interest rates. What’s more, B.C. is the only province where the average savings rate is negative.

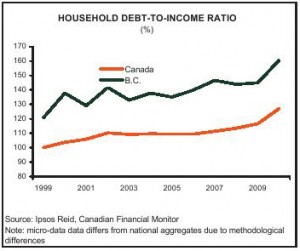

None of this is new, however, as the province has systematically been the most vulnerable since the start of our data series in 1999. The structural nature of this challenge suggests that there maybe factors at play that are not being captured in the aggregate data. For example, the province’s relatively large economic reliance on its service sector and self-employment – two areas that tend to have higher-than-average incidences of non-reported income – might be superficially driving down income and driving up the various sub-index readings.

In addition, B.C. households appear to have adopted coping mechanisms, such as renting out basement suites, which might not be fully factored into the income side. Even if these factors are part of the story, they don’t address the fact that British Columbia’s index level has recorded the second fastest rate of increase among the provinces over the past half decade.

Higher interest rates over the next few years threaten to leave as many as one in ten households in B.C. in a position of financial stress. On the plus side, rapidly-appreciating home prices in the province has left the debt-to-asset ratio – a metric of household leverage – below the Canadian average. Still, with the home price-to-income ratio pointing to some ongoing over-valuation in the housing market, stable B.C. home values are far from assured.